02 December 2019

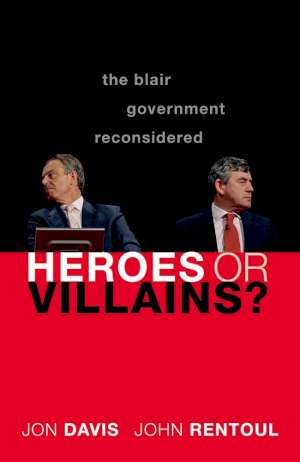

Heroes or Villains?

The Blair Government reconsidered

Jon Davis and John Rentoul

2019, Oxford University Press, 356 pages,

ISBN 9780199608850

Reviewer: Mario Pisani

This is an impressive new analysis of the conduct of UK government over the period 1997 to 2007, when Tony Blair was Prime Minister and Gordon Brown was Chancellor of the Exchequer. While there have been numerous treatments of this subject, the authors of Heroes Or Villains? manage to offer something here which feels genuinely original and different.

This fresh new approach is the result of the breadth of new material acquired as part of the authors’ teaching initiatives. Jon Davis is Lecturer of Contemporary History at King’s College London and Director of The Strand Group at King’s, while John Rentoul is the Chief Political Commentator at The Independent and Visiting Professor at King’s College London. Since 2008, they have been teaching undergraduate and postgraduate courses about the Blair government, first at Queen Mary University of London and later at King’s College London (declaration: I also currently hold a visiting position at King’s). Through their teaching, Davis and Rentoul have not only had the opportunity to analyse in-depth the Blair-Brown years, they have also had access to a wide selection of key protagonists who worked in government at that time. The list reads as a who’s who of the higher echelons of the UK Civil Service in the late 1990s and early 2000s: Robin Butler, Richard Wilson and Gus O’Donnell to name just a few.

The book is organised into five chapters, which reflect the key themes of the Blair years. The first chapter looks at the dynamics between Prime Minister Blair and Chancellor Brown. The authors explain the origins of what would later become the central political relationship of its time – tracing this back to their entry into parliament in the 1980s and the so-called “Granita deal” in 1994. A strong recurring motif is the idea that the personal relationship between the two men resulted in the creation of “parties within the party” – such that the government was effectively run by a coalition between the Blairites and the Brownites.

The next two chapters look at specific aspects of the conduct of government in this period. Chapter 2 focuses on the way in which Blair worked with the rest of Cabinet. The received wisdom is that the Blair years saw the death of collective government and increased use of informal decision-making structures (what has since become known as “sofa government”). The authors’ analysis shows that the reality was more nuanced than that, with Blair not necessarily acting in ways that were unconstitutional or out or line with past practice. Chapter 3 looks at the role of Special Advisers (SpAds) or politically-appointed government officials. Some of these SpAds became as well-known as the very ministers they worked for: Alastair Campbell, Ed Balls or Charlie Wheelan. Thanks to the evidence from interviews, the reader can explore the nature of the relationship between the permanent civil service and the political appointees. A strong take-away from this chapter is that the hypothesis that more power for the SpAds meant an undermining of the work of civil servants is rejected as too simplistic.

For SPE members in particular the chapter focusing on the activities of HM Treasury under Gordon Brown will be of significant interest. This is partly because there is relatively less written about this topic, in comparison with what has been written, for example, about No10 and Tony Blair’s premiership. But it is also because of the incredibly insightful interviews given by top Treasury officials from that time which informs the narrative of this book. These interviews feature Terry Burns and Nicholas Macpherson (former Treasury Permanent Secretaries), Jeremy Heywood (former Cabinet Secretary), Dave Ramsden (former Chief Economic Adviser) and, most prominent of all, Ed Balls – the man who was often described as “the deputy Chancellor”. This chapter covers some of the key landmark moments in economic policy-making of the Brown years as Chancellor. The granting of operational independence on monetary policy to the Bank of England in 1997 features prominently, and the story is told from interesting new angles. We also get analysis of the five euro tests in 2003, public service reform, and the Treasury’s preparedness in 2007 for the financial crisis.

Across the various chapters, the authors achieve the delicate balancing act of offering historical context without going off-piste. For example, we get – at various points in the narrative – the following: a potted history of the concept of cabinet government, a look at past tensions between No10 and No11 Downing Street, a history of the post of Cabinet Secretary, and an analysis of where the post-war PMs stood in the prime-ministerial versus collective governance spectrum.

In Heroes Or Villains the authors expertly apply their analysis of the Blair Government on the wider canvas of history, and they manage to do so with a gentle touch. They also show the huge synergies that can extracted by exploiting the links between academic teaching and historical research. In doing so, Davis and Rentoul show how to make contemporary history both insightful and engaging.